Pakay, a significant photographer, recorded a little-known part of Baldwin's life

ESSAY

by Miraç Süzgün RC16 and Donald Spanel

“And there was something so artless in this smile that I had to smile back.” ~ Giovanni’s Room, James Baldwin

Sedat Pakay RA 64 at James Baldwin's apartment while filming From Another Place, 1970.

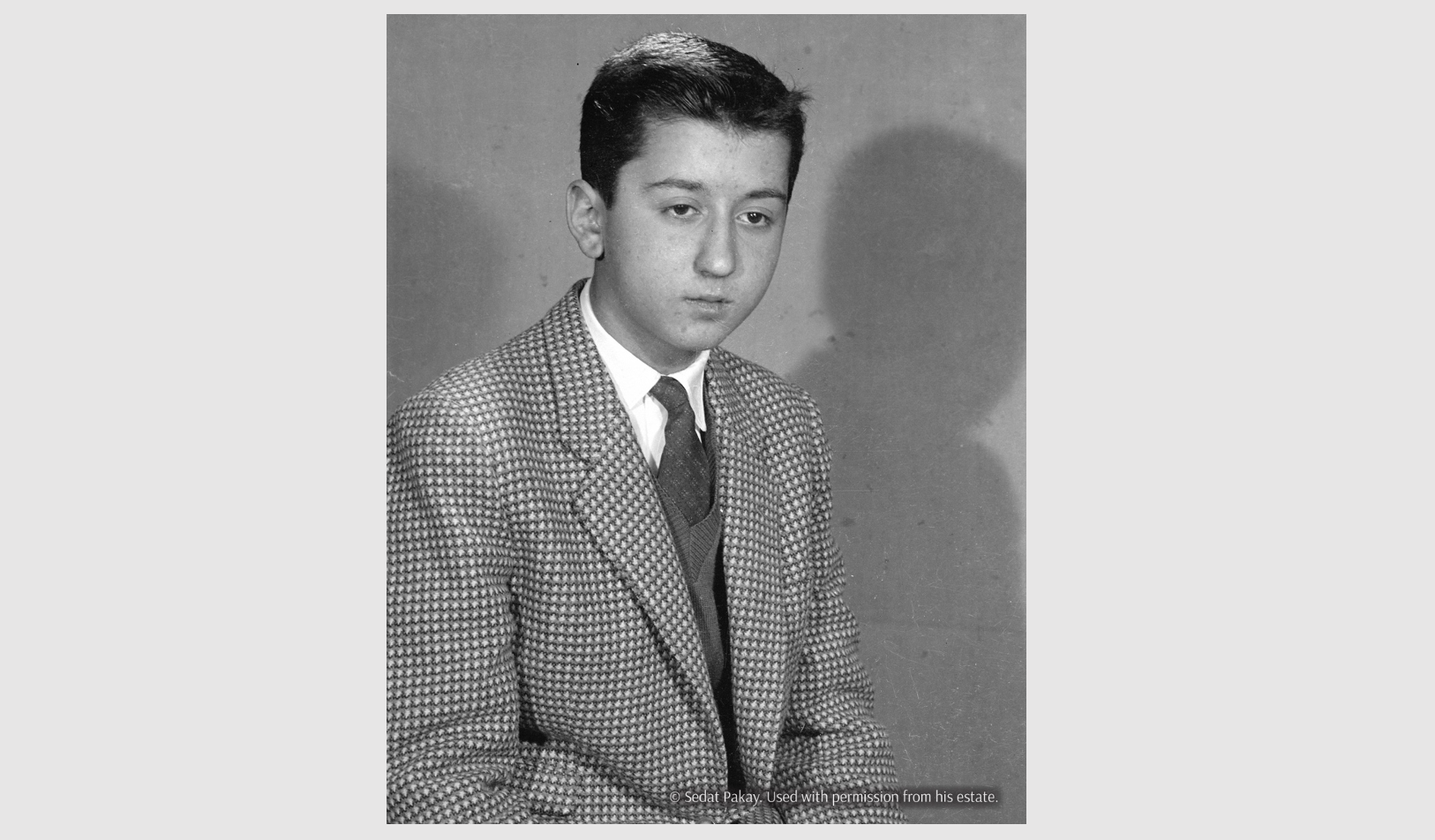

In 1964, a nineteen-year-old Turkish engineering student named Sedat Pakay (1945–2017, RA 64) read an article in a local newspaper that would alter the course of his life. The article announced the forthcoming arrival of the renowned American writer James Baldwin to Istanbul. Baldwin (1924–1987) was already a well-known literary figure and a prominent advocate for the Civil Rights movement in the United States. What captured Pakay’s attention in the article, as well as another about Baldwin which he saw soon thereafter in a 1964 issue of Look magazine at the school library, was neither his literary fame nor his political activism. As Pakay later recalled, it was the intricate “topography” of Baldwin’s face—a visage marked by large circular eyes, anxiety-incised brow, and infectious smile.

Pakay knew nothing of Baldwin or his work apart from what he had read in these two articles, but as a self-taught photographer with a passion for portraiture, he felt an irresistible urge to meet and photograph Baldwin, whose face bore the scars of life’s hardships. To him, Baldwin’s face revealed volumes—about pain, love, struggle, and discovery. As Baldwin was to words, Pakay was to visuals; he was determined to capture the essence of the person behind that magnetic face. That determination belied his usually quiet, shy, and reserved demeanor, in the recollections of his classmates İsmail Saltuk RC ENG 68 and Orhan Demirdağ RA 65.

There were two obvious challenges: ascertaining where Baldwin was staying and securing an introduction. As a nineteen-year-old amateur with no credentials other than talent and ambition, Pakay required someone to intervene. Özer Kabaş RC 57, his art-history teacher, served that role. Baldwin, he said, was to be the guest of his friends Engin Cezzar RC 55 and Gülriz Sururi, both acclaimed stage actors in Turkey in the 1960s.

Kabaş had received his BFA and MFA degrees from Yale University in 1960 and 1962, respectively, studying under Josef Albers and Jack Tworkov. It was there that he met Cezzar, who was studying acting at the drama school. Cezzar had previously befriended Baldwin at the Actors Studio in New York in the 1950s when he was cast as Giovanni in Baldwin’s adaptation of his second novel, Giovanni’s Room. The two bonded quickly and became close friends. After returning to Turkey, Cezzar exchanged letters with Baldwin, often inviting him to Istanbul. In October of 1961, following a demoralizing trip to Israel, Baldwin showed up unannounced on the doorstep of Cezzar and Sururi’s small apartment in Taksim.

Baldwin was smitten by the warm welcome and reception he received. Having sought refuge from the racial and societal pressures of his homeland, he immediately felt at ease and peace in Istanbul. With its beauty, diversity, and chaos, Istanbul reminded him of Harlem in New York City, the place where he had grown up. The intellectual and artistic circles of Istanbul provided him with a haven, free from discrimination, while embracing him as an artist, as an activist, and, most importantly, as an individual. Baldwin’s extended residencies in Istanbul throughout much of the 1960s account for his most productive period. He wrote, in part or in entirety or revised, Another Country, The Fire Next Time, Blues for Mister Charlie, Going to Meet the Man, Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, One Day When I Was Lost, and No Name in the Street. He made his début as theater director with the Turkish production of John Herbert’s Fortune and Men’s Eyes.

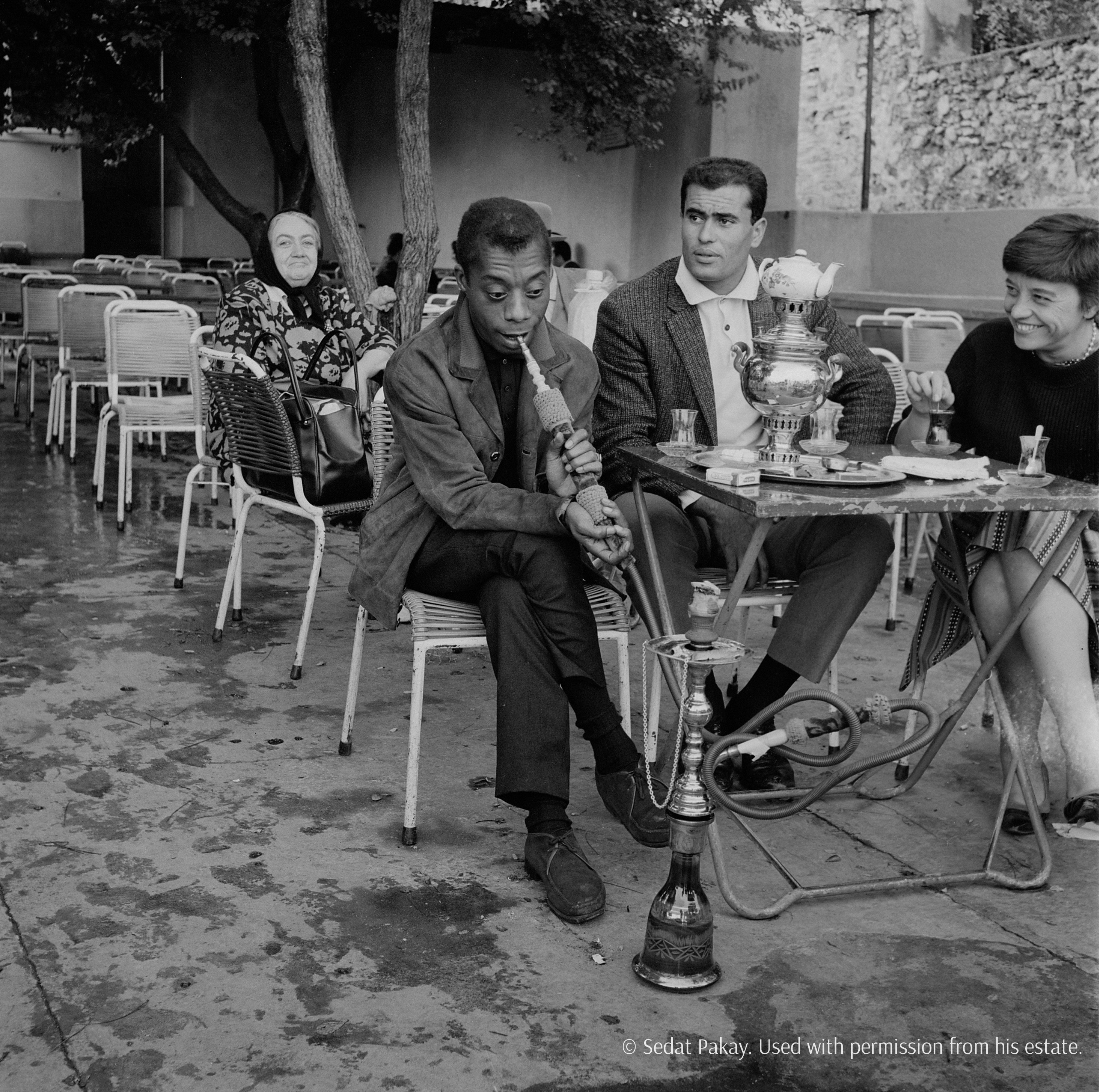

Baldwin with a nargile at a tea garden

During his initial visits to Turkey, Cezzar and Sururi were crucial in forming Baldwin’s social network in Istanbul. Kabaş therefore rang his friend Cezzar and secured an invitation for Pakay to meet Baldwin at a party that Cezzar and Sururi were hosting at their flat. Rolleiflex in tow, Pakay arrived and found Baldwin writing at the kitchen counter. Bemused but amused, Baldwin agreed.

Pakay’s desire to take photographs appealed to Baldwin on several levels. Since childhood he had internalized the taunts of his abusive stepfather who had called him “ugly”. That Pakay found him photogenic was refreshing and redemptive. He was gratified to have such a youthful admirer, so far from the United States, and so unfamiliar with his work. Baldwin longed for appreciation as an individual, not as a celebrity. Pakay showed that deep appreciation and genuine interest.

The encounter at Cezzar and Sururi’s party was the beginning of a profound friendship. Pakay accompanied Baldwin on many excursions around Istanbul, often serving as his tour guide. From the historic Sultanahmet district to the Emirgan Park and Kilyos on the shores of the Black Sea, these two kindred spirits embarked upon countless adventures together. At his family’s summer home in Tarabya, Pakay hosted a lunch for Baldwin and his friends, among them David Leeming, who had been Pakay’s teacher of English literature at RA and who served as Baldwin’s personal assistant in the 1960s, and Bertice Reading, who was a famous singer and actor at the time and one of Baldwin’s closest friends while he was in Istanbul.

Baldwin (front, right) at a party at the Pakay home in Tarabya, 1966.

But for Pakay’s photographs, this transformative period in the life of one of America’s preeminent writers would remain obscure. Though Baldwin cherished his time in Istanbul, written records of his experiences are sparse, in marked contrast to his time in Paris. His intention to write an article about Turkey is evident from his correspondence with his literary agent at the time, Robert Mills, but this project did not come to pass. In several interviews, Baldwin briefly alludes to Turkey, and in his novel Just Above My Head, the narrator recalls his brother flirting with the idea of purchasing a home in Istanbul, mirroring Baldwin’s own fleeting contemplation. Yet these notions remain unrealized, with the narrator of the novel even dismissing them as “nutty”. Overall, references to Istanbul in Baldwin’s fiction are notably wanting.

Baldwin underneath the chandelier of the Blue Mosque

Pakay’s photographs of Baldwin’s Istanbul sojourns provide more than a visual record of the writer’s life in the 1960s; they unveil the essence of his humanity. Baldwin’s daily routine in Istanbul emerges as simple yet cheerful: a dance between writing, exploration, and socializing. As one analyzes these photographs, a sense of wonder blossoms—not only at Baldwin’s welcome in Istanbul but also at the depths and breadth of his human connections.

These photographs depict the unfamiliar story of Baldwin’s life in Istanbul, where the cacophony of his fame faded into the backdrop. Baldwin could frequent a café or teahouse without harassment, stroll through the long and narrow streets of Taksim greeted by strangers, and even find himself in a moment where a young mother offered her child as if seeking his benediction.

For Baldwin, these experiences were profound, affirming his belief in the transformative power of travel and the profound impact it can have on one’s perspective. As Baldwin considered himself a witness to his era, Pakay was witness to him in that role, capturing the moments that would shape the writer’s creative output during his sojourn in Istanbul. Through Pakay’s lens, the focus shifted from James Baldwin, the celebrated writer, to Jimmy—revealing the humanity that binds us all, regardless of fame or fortune.

Baldwin reaching out to an infant offered by its mother

Their friendship culminated in the creation of the short documentary James Baldwin: From Another Place, made in 1970, which was largely responsible for the recognition Pakay enjoyed during his lifetime. The film’s opening scenes are both intimate and revealing, capturing Baldwin as he emerges from slumber, with the Bosphorus in the background. It indicates the trust Pakay enjoyed with Baldwin. The film’s narration, voiced entirely by Baldwin, draws from interviews conducted by Pakay. Within the documentary, Baldwin concisely but eloquently articulates a recurring theme in his life: the imperative to distance himself from America to gain a clearer perspective about both his country and himself.

While Pakay interviewed Baldwin for an additional forty-eight minutes as part of his film, much of this conversation remains unpublished. Kim Fortuny, a Baldwin scholar at Boğaziçi University, has cited and discussed some segments. According to Fortuny, Baldwin speaks of Turkey’s struggle to grapple with the vestiges of its once-glorious empire, highlighting that it is challenging to transition from the memory of a rich past to the demands of the present. As an outsider, Baldwin seems to have observed the profound path that Turkey was undertaking, sensing an energy that may hold far-reaching consequences in the Middle East and elsewhere.

In 1966, in a corridor within the engineering school at Robert College, several of Pakay’s photographs were displayed as part of a small exhibition showcasing his work. Among the photographs were portraits of James Baldwin and Aliye Berger, an artist and host of illustrious salons in the Pera district. These photographs caught the attention of John Freely, an American teacher at Robert College and later at Boğaziçi University. He had a passion for Turkish history, culture, art, and architecture. Though he had a long and distinguished career teaching subjects ranging from math and physics to the history of science, his true devotion lay in exploring Turkey’s rich heritage. He considered himself a spiritual successor to the Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi (1611–c.1683), renowned for his monumental travel narrative, the Seyahatname (Book of Travels). Of its ten volumes, the second and longest describes Istanbul, encompassing everything from the grandeur of Topkapı Palace to the squalor of meyhaneler, the local taverns. Freely embarked upon an ambitious mission to rediscover the places Evliya had explored and to find their contemporary counterparts. Every Saturday, he ventured into the city with his wife and three young children, examining prominent landmarks—not only the mosques and palaces but also the flea markets, the neighborhoods of the Roma, and the many descendants of Evliya’s taverns.

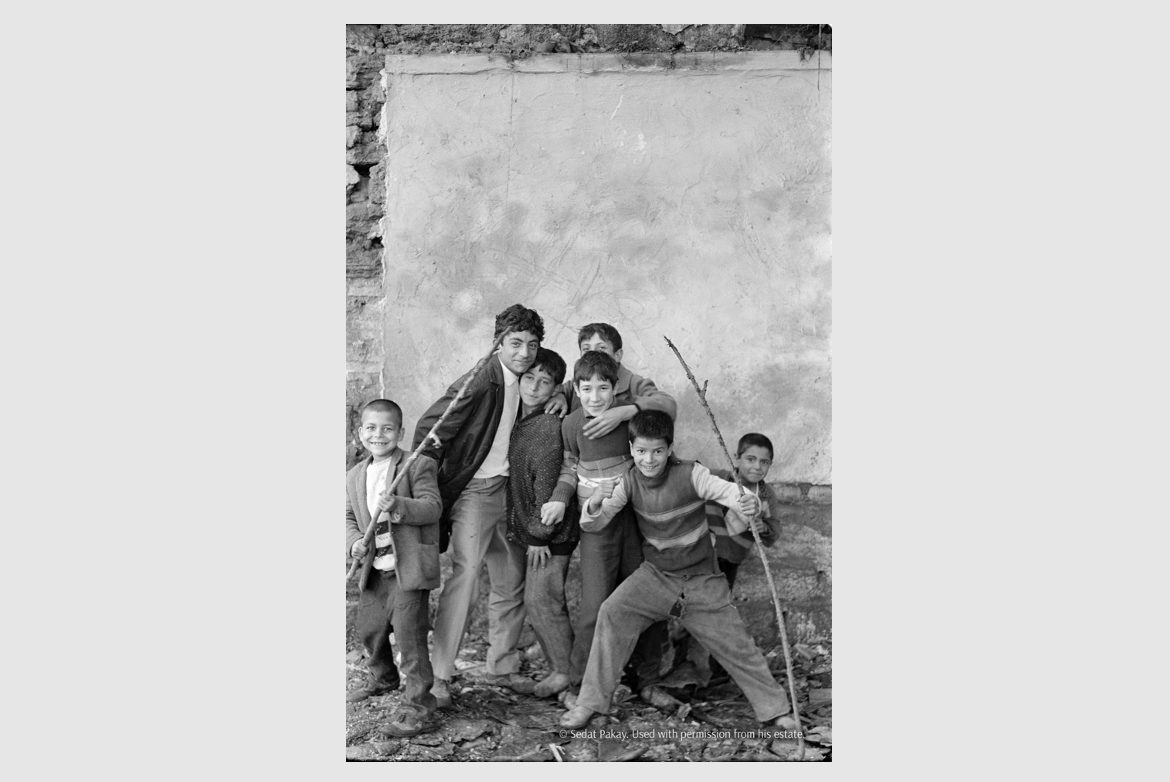

A group of Romani boys

As Freely began crafting an updated narrative about Istanbul, he realized that Pakay was the perfect photographer to illustrate his book. The conviction grew stronger when Pakay showed his extensive portfolio of street photography, revealing the lesser-known corners of Istanbul’s historical Fatih district. Freely was particularly drawn to Pakay’s focus on the marginalized communities, from itinerant vendors and small shopkeepers to the oarsmen navigating the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, and the Roma children playing in the alleys. Always eager to nurture the talents of students at Robert College and the American College for Girls, Freely invited Pakay to join him on his walks.

Apart from the late photojournalist Ara Güler, no other photographer had captured Istanbul’s marginalized communities with the same sensitivity and insight as Pakay. While he always maintained that his primary goal was to capture compelling images, a melioristic interpretation is possible. His subjects, though downtrodden and world-weary, exude resilience. In many ways these individuals appear nobler than the elite. While others often overlooked Istanbul’s large Roma population, Pakay enjoyed their company. His photographs of a group of young Roma boys radiate their happiness, both among themselves and as the center of attention. No one could guess that the municipal government had recently razed their homes in Sulukule.

Freely and Pakay’s book, Stamboul Sketches, was published in 1974 by a small press in Istanbul in a limited edition of one thousand copies. The tight budget is manifest in the poor-quality cover, the binding, and especially the paper, which rendered both the typeface and photographs murky. The book did not receive the attention it deserved, though it did remain in memory, and forty years later it was republished in an elegant edition in London, complete with a new afterword by Maureen Freely ACG 71, John Freely’s eldest daughter and a prominent translator of Turkish literature into English. However, Stamboul Sketches has yet to gain the wider recognition it merits, as it is one of the most intimate, heartfelt, and vivid accounts of Istanbul since the Seyahatname.

Pakay’s journey took an unexpected turn when Özer Kabaş, his art-history teacher, persuaded him to shift his focus from engineering to the arts, allowing him to develop his passion for photography. Kabaş firmly believed that Pakay should apply to Yale’s prestigious MFA program. His conviction about Pakay’s talent was so firm that he sent an unsolicited letter of recommendation to a dean at Yale. In 1964, Pakay applied and was accepted, with the condition that he defer his enrollment until 1966 due to his young age. Pakay readily agreed, which provided him with more time to take photographs of Baldwin and continue his street photography, both with and without John Freely.

Sedat Pakay RA 64 at Robert Academy

Pakay left RC in 1966 to pursue his studies at Yale without graduating. To secure his student visa for the United States, he needed an American citizen to sign an affidavit, guaranteeing financial support if necessary. As Yale offered Pakay a scholarship, this was a mere formality, but he turned to Baldwin for assistance. Baldwin, in a show of support and friendship, agreed to accompany Pakay to the American consulate. In his later years, Pakay fondly recalled a wish that he had his camera with him, because the image of Baldwin, a slight figure, walking between two towering Marines guarding the consulate entrance was an unforgettable scene.

Pakay’s application to Yale included selections from his diverse portfolio, which eventually landed on the desk of the photographer Walker Evans. Evans had been appointed as a professor in the Department of Graphic Design within Yale’s School of Art and Architecture in 1965 and particularly appreciated Pakay’s street photography. Even though Pakay’s interest was in portraiture, Evans recognized their shared aesthetic in the everyday vernacular, showcasing the overlooked and unpretentious facets of life. This connection between Pakay and Evans is important because Evans’s striking black-and-white photographs of the rural working-class families at the height of the Great Depression had similarly played a crucial role in, if it did not entirely define, his artistic career. Evans developed an esteem for Pakay’s abilities that he rarely bestowed on his other students.

During his time at Yale, Pakay’s focus gradually shifted toward documentary filmmaking, and he returned the favor to Evans by creating two documentaries about him. The first, Walker Evans: His Time, His Presence, His Silence, went nowhere, but the second, Walker Evans/America, which was produced long after Evans’s death in 1975, was eventually broadcast by the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) in 2000.

After graduation from Yale, Pakay remained in the United States. His next project centered on the artist and educator Josef Albers, who had previously chaired Yale’s art department and was also a mentor of Pakay’s art-history teacher Kabaş. Although Albers had left several years before Pakay’s enrollment, his influence and legacy remained. Recognizing an opportunity, Pakay proposed a documentary about Josef and his wife, Anni Albers, a textile artist and printmaker. Josef and Anni Albers: Art Is Everywhere, became the first film to focus on both artists and was broadcast by PBS in 2006.

In the fall of 1968, following his graduation from Yale, Pakay received an invitation from Skidmore College, a women’s college in Saratoga Springs, New York. The college's class of 1969 sought to break away from the conventions of a yearbook and aimed to make a statement reflecting the transformative spirit of the late 1960s. Each graduating senior was granted the freedom to shape the content and format of her photograph. Pakay embraced this approach, following the students around the campus and capturing their personalities in a variety of costumes and settings.

The result of this months-long effort was a collection of over 13,000 black-and-white portraits. Liz Roman Gallese, the executive director of the acclaimed documentary which focuses on the creation of this unusual yearbook, titled Women of '69, Unboxed, aptly describes this collective outcome as “Yearbox,” a compilation of playful, expressive, and occasionally rebellious portraits.

Sedat Pakay's journey as a photographer and filmmaker took him on a remarkable odyssey, capturing the essence of numerous luminaries from various walks of life. His lens immortalized not only iconic figures like Baldwin, Evans, and Albers, but also Andy Warhol, Doris Lessing, Gordon Parks, Mark Rothko, and Ronald Reagan. Pakay's diverse body of work extended beyond photography, as he ventured into the world of film, serving as visual consultant to projects like Malcolm X for Warner Brothers in collaboration with screenwriter and producer Arnold Perl. His photographs are in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, DC, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and Istanbul Modern, among others. Yet, Pakay’s extensive archive still requires a home that will provide conservation and cataloging.

For a selection of the Baldwin photographs please visit sedatpakay.com.

In paying tribute to Sedat Pakay's indelible contributions, this article stands as a testament to his enduring artistry, and it is dedicated to his beloved family: his wife, Kathleen; his son, Timur; his daughter-in-law, Stephanie; and his grandchildren, Cecilia and Oliver.

Published January 2024